You can find a copy of the issue in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, West Virginia, Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, Tennessee, Alabama, Michigan, Louisiana, Florida, and Texas! At these news stands: http://www.wncmagazine.com/newsstand

Red Clay and Pretty Talk

Written By:

Shari SmithArtwork by:

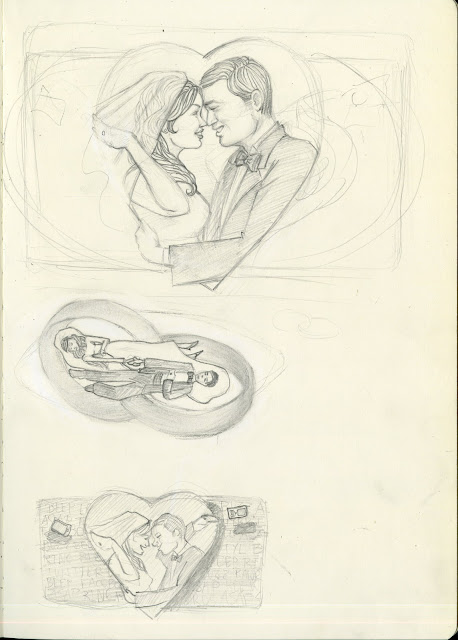

Morgann Daniels| "WNC On My Mind" -Morgann Daniels |

There’s nothing worse than being trapped in a car with a writer from Alabama.

They’re either complaining as to the length of the trip or taking a nervous pill if the speedometer registers above the posted limit. What’s most grating is when they get to waxing rhapsodic about the literary history of their state as if the names Thomas or Reynolds or O. Henry never graced a book cover or crossed their narrow minds. Makes it damn hard to be a Christian.

A few years back, I was driving on Scenic 98, along Mobile Bay, past waterfront houses and grand hotels, with an Alabama writer boy riding shotgun. He took his eyes from the brackish water and postcard view of sailboats and seagulls, turned to me and said, “You’ll move here someday, won’t you, to be near other writers?”

I thought of red clay.

I don’t reckon anybody ever drove through my Carolina town for the view. Unless you’re coming to see your momma, the only reason to take exit 135 off Interstate 40 is to fill up the tank or empty your own. That was pretty much the marketing strategy of my buddy, Jeff, who opened a restaurant out at the highway and named it Boxcar, complete with a ticket window where the hostess takes your name and the number in your party and a dinner entrée called Trolley Tips. They even nailed a fake run of railroad track to the wall behind the salad bar. Weekend tourists don’t come to peep at the leaves, nor do we have any slopes to ski down. Nobody’s making fudge or boiling peanuts and hawking them to the patrons coming to town for the art festival.

We don’t have an art festival.

We have three stoplights, two more than we really need, a place to order flowers for funerals and prom night, and an impressive pack of stray dogs. They’ve defied the efforts of county animal control, breezing past traps baited with steak, and produced at least three litters of puppies, which all found homes despite the gypsy souls of their parentage. We gave up on catching them a long time ago. I was sitting in the police station, by choice not incarceration, when Pam, who answers the phone and decides who gets buzzed in, looked out the window and said, “There go our little bandits,” as they trotted on down the sidewalk on Main Street without care or concern, other than getting to the dumpster behind the Claremont Cafe. We have two banks where the tellers know our names and account numbers by their blessed little hearts. We have a volunteer fire department and an active Lions Club that ran the Jaycees out of town. We have Eddie, the mechanic, who pointed a wrench at me one day and said, “Listen, here. Don’t go lettin’ any of them stupid boyfriends work on this John Deere ever again. It’s mine, you hear? I ain’t fixin’ their mistakes, no more.”

I haven’t cheated on Eddie since.

Town drunks are allowed to walk the streets and sleep where they wish as long as they clean up their empties. Not doing so is just sorry and while sober is not required, respect for the town is. In church, babies are passed and prayers are said for sick folks even if we really don’t like them all that much. I am welcome at each of the five churches in town, expected at none. The men who sit at the back table of the Claremont Cafe will argue for days over the best route to take when driving anywhere outside the state, often over the difference of less than 20 minutes. Everybody comes to watch the Christmas parade, all three blocks of it. We can see the mountains from our kitchen windows, but like many beautiful things, they are out of our reach.

From time to time, people will ask me why I came to Claremont. My answer is that though I came for the wrong reasons, I stayed for the right ones. I am here for the family that circles around me in good times and complete devastation. I am here for the familiarity of finding tulip bulbs in a Dollar General sack outside my back door, dug up and left for me by my neighbor, the best gardener in town; the smell of the heart-stopping grease when the door to the Cafe eases open; the annual telling of the Christmas when the Savior was stolen from a manger scene outside one of our churches, only to be recovered when the waitress at the Waffle House in Hickory called the sheriff and said, “There’s a drunk standing in the parking lot holding baby Jesus and crying.”

Bless his heart.

I am here for the rhythm, the cadence of the language of rural Carolina. It plays like music in my head. Tim Yount is wicked smart with a lightning quick wit, though not much for tending to his own yard work. He reads three newspapers every morning, can quote Updike like he wrote it, and spent last election day working the polls to see that a good judge stayed on the bench. But, on a particularly bad day for both of us, though for different reasons, Tim said to me, “Sugar, we might should pitch a good drunk.”

All men should talk pretty that-a-way.

I don’t complain about Proctor & Gamble’s failure to invent laundry soap that will remove the red clay from my clothing. I wear it, glad it won’t come out. There’s no separation in my mind between this land and these people—these people who punch clocks and line up at sewing machines to stitch together sofa cushions for other families to sit on; this place where you recognize a furniture builder by the cracks in his front teeth from holding tacks in his mouth trying to go faster—making his quota, but missing his aim when bringing the magnetic hammer to his lips. Jerry Hoke’s birdhouses, Miss Peggy’s pound cake, the quilts of the Ladies of St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, Gary Sigmon’s ’66 GTO that outran the law and brought him on home, time and again—each one a good story that should be told, and deserves to be remembered. A writer doesn’t need to be with other writers. We need to be where there are stories to tell.

Driving along that bayside highway, I looked at the boardwalk, at women in oversize sunglasses, wearing capri pants with sweaters tied around their necks. Remembering the red stains on the frayed hem of my jeans, I said, “No, I’m a foothills girl. I’ll stay in Carolina with my people.”

Shari Smith is currently working on a nonfiction book about her adopted hometown of Claremont.

The Potato Patch

Written By:

Brian Lee KnoppPhotographs by:

Morgann Daniels| "Potato Patch" -Morgann Daniels |

Amazing how a twenty- by fifty-foot strip of hard clay soil, cut off by a bold creek on one end and a dead-end road on the other, could mean so much.

I live on a small farm that’s steep as a mule’s face and configured like a derby hat that’s had the back half cut away. The only available flat land lies like the hat’s narrow brim, curving along the contour of the aforementioned bold creek that divides my property from my neighbor’s. Our house clings to the looming wooded hillside like a buckle on the hatband. When my wife and I bought our place in Yancey County back in the ’80s, the only existing rights-of-way were a walk bridge thirty feet long and a bushel-basket wide, and an oak-planked drive bridge that lay at the bottom of an abrupt hill some three hundred feet from the house.

My neighbor had this nice level strip of land that led to what could be a natural driveway of bottomland along our side of the creek and right up to our house. The strip had potatoes planted, but nothing else. Tangles of catbrier and blackberry cane coiled along the sides. Bee balm and stinging nettle settled thickly near the border with the creek.

The potato patch appeared to profit him little. But it promised us a safer, more efficient way to bring firewood closer to the home that would burn it for winter warmth.

Everybody called my neighbor “Sonny,” even though he was in his 60s by then. A tall man, all nose, sinews, and cigarettes, Sonny didn’t suffer fools or beggars. Or flatlanders who might turn out to be both.

We waited two years before asking.

“Sonny, do you think you might want to sell that little potato patch to us so we can throw a bridge across it?”

His craggy face darkened and his mouth folded into layers of resistance.

“Naw, I don’t think I would.”

We let the matter be.

A few years later, the matter resurrected itself. I had rebuilt the walk bridge, but only wide enough for three men and a boy to carry a woodstove across it, which happened twice. I had almost driven my truck off the icy plank bridge several winters in a row, too. I’ll not detail our yearly ordeal of using mules to drag down—and humans to hand carry—firewood logs to the house, except to point out that “death by mule” is excluded by many a homeowner’s insurance policy.

It was too much aggravation. It would be simpler to buy split firewood and truck it over that flat potato patch and haul the wood right up to the house.

I dearly desired that potato patch.

One summer, I saw Sonny sneaking toward the roadside corner of the potato patch. He had hornet spray in one hand, a small gas can in the other. I noticed raised red blotches on his leathery arms and one centered on his forehead.

“’Lo, there, Sonny. What are you into?”

“’Lo, Brian. Got a big yellerjackets’ nest there. Them sorry boogers deviled me for the last time. I got somethin’ right here they’ll remember me by!”

I watched him spray the hole, splash it with gas, then toss his cigarette on it. There was a huff of ignition, a ball of flame that rolled away and blended with the summer’s heat, followed by a few stray wisps of smoke that arced toward the ground, wiggled a bit, then curled up dead.

I shared his satisfaction. Then I asked him about the potato patch.

“You ever sell your potatoes?”

“Naw. Wouldn’t make nothin’ if I did. The big stores sell them ones from Ida-ho so cheap it’s un-real.”

“You just grow them for yourself?”

“Yep. A man won’t starve so long as he’s got taters dug in somewheres.”

“Well, if a man was to pay you three times the value of all the potatoes you could ever dig up in a year—just so he could get at his firewood—would you take it?”

He frowned and spat.

“Loggin’ would compact the soil. Hit would be ruined.”

I fought back.

“But no more than your tractor’s wheels do every year?”

“I think it would. Nosir, I wouldn’t allow it.”

The score: Sonny 2, Me 0.

Years later, Sonny trapped a ’coon down there. He was 80 by then. He was scared to dispose of it because he was sure it was rabid, which he pronounced “ray-bid.” I got rid of it for him. He was grateful. He got talkative and lapsed into telling hunting tales.

I sensed another opportunity. It was now or never.

In my dreams, I would gamble everything, promise anything. I’d smother him with truckloads of organic potatoes, pave the patch’s borders with hand-painted tiles bearing the likenesses of Sonny and Dale Earnhardt, enrich the soil with the finest manure from champion show cattle.

But face to face with the man, I could only offer this.

“Sonny, I’d like to buy that potato patch from you. Name your cash price, and I’ll gladly pay it.”

He was silent for too long. His face gave away nothing.

When he finally spoke, he looked at his feet as it came out softly, steadily—history aimed at the ground.

“Papaw John grew his taters here. Taters had always been grown here. ’Backer and corn everywhere else, but taters from right here.”

And then his final word on the matter.

“You just want this piece of land. You don’t need it. But I do. And I’ll not sell it for love nor money.”

He’d made his point. I won’t ask him again.

You got to keep straight what you want from what you need.

Brian Lee Knopp is a former private investigator, criminal defense investigator, and professional sheep shearer. He is the author of the bestselling memoir Mayhem in Mayberry: Misadventures of a P.I. in Southern Appalachia.

|

| For an article about Ramps. |

|

| For an article about being transplanted from Florida to North Carolina. |

|

| The article about a man and his potato patch. |

|

| For an article about a woman and the small town she lives in. |